Things haven't looked this good for UK football since the Bear Bryant era

If you find yourself constantly refreshing the football forum or the House of Blue at CatsIllustrated.com, waiting for word of the latest commitment or frequently discussing what just happened at camp or on a player's visit, you've got a bad case of football fever.

There have always been football-obsessed Kentucky fans who throw inhibitions into the wind and believe that anything's possible, but for most of modern history it probably would have been fair to call those types (perhaps you?) naive or even flat-out homers.

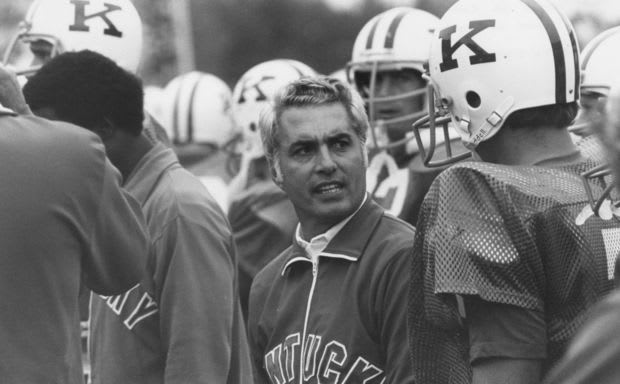

You may still be naive on certain points, and you're probably no less a homer, but at this moment in history your optimism is more justified than ever. That's because things haven't looked this good for Kentucky football, in almost every respect, since the late 1970's. And when you consider the inglorious end that mini-run in Lexington came to, this might be the most legitimately promising era for the Cats since the days of Bear Bryant.

Let's be honest. On the one hand, the fact that a person could even say that should be a humbling realization. For most of Kentucky's history, as you well know and as you don't need or want to hear, things have looked decidedly worse than this.

In truth, things have usually looked very bad, no matter how optimistic the biggest optimists have always been. Compared to results, realistic expectations and outside forecasts for other SEC programs, Kentucky has almost been playing on a completely different (lower) level for most of the decades since the Bear roamed the sidelines.

OTHER 'WINDOWS OF OPPORTUNITY' FOR KENTUCKY FOOTBALL

There have certainly been moments when hope seemed the rational response to events on the field (or perhaps off it).

1. Rich Brooks' run and five-straight bowl games. This would clearly be the most recent instance of Kentucky football appearing poised to change the game in a very positive way. And, frankly, in some ways this stretch of history had more substance to it than some of the others you'll read about soon.

For starters, Brooks did things the right way. During the time periods you'll see in examples 2 and 4, for instance, Kentucky football was not doing things the right way. Not many people knew that at the time, but when you cheat, you get an asterisk. Everywhere. The record book and the collective memory of sports fans say that Brooks did things the right way, and that counts for something, especially when you inherited a program that was plagued by people who didn't do things the right way and had a huge hill to climb to respectability.

Brooks' era's signature moment(s): Perhaps the greatest "moment" in Kentucky football history, aside from an early 50's major bowl win over Oklahoma, was the 43-37 three overtime win over No. 1 (and future BCS champion) Louisiana State. This era also included bowl wins against Clemson, Florida State and East Carolina, two wins against Georgia (one on the road) and a road victory at Auburn. Plus, of course, five straight bowls. And who can forget "Stevie got loose!"?

Why it didn't last: Kentucky failed to capitalize on this "moment" in history because the recruiting never substantially improved, lost leadership was not fully replaced (there were two waves of leaders; first Wesley Woodyard, Jacob Tamme, Andre Woodson, Keenan Burton, etc., and later Randall Cobb, who probably had the football-equivalent of a Mike Trout baseball "WAR," single-handedly winning several games). That success was not sustained into the next coach's longevity doesn't mean this era was any less impressive. On the contrary, the regression under Joker Phillips was a quick reminder of how hard it was to do what Brooks did. But the point remains, success on one level (on the field, getting to the postseason namely) was not matched by other successes that were probably essential to the program's continued growth.

Dicky Lyons told CatsIllustrated.com more than a year ago that he doesn't believe Kentucky went outside the program enough, in this era, to hire the best or brightest coaches that could have furthered the program's growth. Agree or disagree, the biggest example of this would be the person of Phillips himself, at one point the "head coach in waiting," that role that closed off the possibility of an outside hire and the momentum bump that often accompanies it.

Also, the athletics department (for whatever reason, blame is pointless right now) didn't make the kinds of investments that an SEC-level program needed to make in facilities, coach salaries, etc. Brooks played and won at Moneyball, so to speak, and against the odds. But we can't forget that "against the odds," part. The house, in the long run, always wins.

What we can learn: Kentucky can win by overachieving, by evaluating recruits and retaining players so well that they maximize the potential of a given roster, even for multiple years. But for real, transformative change to occur, the best path is on-field success (however it comes; with talent, with a system, whatever) that is followed or happens simultaneous to an uptick in talent coming into the program.

2. The Tim Couch era. The stadium expanded, the scoreboard lit up, the Air Raid sirens seems to generate euphoric, optimism-inducing brainwaves for those fans who watched touchdown after touchdown after touchdown, no matter how many sacks were surrendered or how touchdowns Tennessee or Florida scored.

The Couch era's signature moment(s): There's the national attention and fan interest that came from Hal Mumme's offense itself -- and let's be honest, it was really exciting, especially since Big XII football hadn't yet taken over college football; heck, the Air Raid wasn't even in the Big XII yet.

But the biggest moment, in real terms, was the 1998 Outback Bowl appearance against Penn State. Kentucky only mustered 14 points in that game, and lost to the Nittany Lions by a solid margin. But the Cats were on a big national stage, the subject of plenty of conversation, and they had a reputation for something, and the something was regarded as pretty cool. People in Texas, California and Florida, people who love football, had a reason to tune in to watch Kentucky football, because Kentucky football was a football laboratory on the cutting edge of experimentation.

There were more on-field accomplishments, including some impressive SEC wins and some real blowouts (including a nearly 70-point outburst against a Louisville that wasn't the Louisville of today).

There was the expansion of Commonwealth Stadium and, for a time, the apparent (turns out, the illusion) recruiting successes that might have helped Kentucky climb the SEC ladder and into greater national respectability.

Why it didn't last: For starters, they cheated. That doomed them in the big picture. That doomed any possibility of sustaining the kind of success, with the Air Raid, that Mike Leach would go on to have at Texas Tech. Kentucky didn't become Texas Tech because, more than anything, they didn't follow the rules.

But they also didn't improve the defense. Some of that is because it's hard to have a good defense when you run that kind of offense, although smart football people now know that "good defense" is really less about traditional big stat categories (like PPG, YPG, etc) than about playing into your preferred tempo and doing what you need to do to win in the big picture (whether it's forcing the offense to drive long fields, preventing long plays, forcing turnovers, etc).

Still, by no measure did Kentucky's defense improve enough, spanning multiple seasons, to be respectable at an SEC level. Coupled with the cheating, which brought on shame and crippling sanctions, this was another big factor. Perhaps another factor was, simply enough, time. Kentucky was winning with some talented players but also with a system. They were doing something new and opponents didn't have long enough, in many cases, to prepare for them. But over time, as they lost all the games to far superior opponents, the 50/50 games started to go the other way, too, as opponents did catch on to what Kentucky was doing a little more. That early Air Raid's success was also a lot easier to manufacture when your quarterback, the most important player on any team in any sport, is the future No. 1 pick in the NFL Draft.

What we can learn: Play by the rules or, chances are, you're going to get caught. Back then, sanctions were more crippling than they are today. Since those UK football sanctions football programs across the country have learned to cope with and even to continue to succeed amid scholarship restrictions and other NCAA penalties. But back then, the sanctions levied on UK were debilitating. Follow the rules.

Also, a system doesn't guarantee sustained success. Paul Johnson has sustained a pretty solid level of success at Georgia Tech with a system that's just as "gimmicky" (this is unfair, because every coach has a system) as Mumme's Air Raid, but simply doing what nobody else is doing doesn't guarantee success. Mumme's demise proves that, and it wasn't only the cheating.

This also doesn't mean that running a conventional offense and defense will guarantee success, but it should cause us to tap the brakes, a little, on suggestions that a system is ever "the solution."

3. Jerry Claiborne's 1984 team (9-3 record). This example pales in comparison to the others on this list because this team, however successful it was, turned out to be a kind of island of good fortune sandwiched between more mediocrity and disappointment. The 1983 team did finish with a winning record (6-5-1) but four losing season (1985-1988) followed those teams. And between the 1977 co-SEC championship team and the '83-84 teams: Nothing but losing records.

It's probably not fair to altogether disregard these teams, but by the most important metrics they were not so much windows of opportunity, in hindsight, but momentary reprieves from "more of the same." Nothing happened before or after this uptick that would have led anyone to believe Kentucky's football fortunes were changing.

Claiborne actually didn't leave the program in the sorry state that his predecessor did, or that Phillips did before Stoops was hired. Claiborne jockeyed for better facilities and he cleaned up the program, leaving it in a somewhat respectable state, but aside from the '84 season the final results at the end of his tenure left something to be desired on the field.

Kentucky's Claiborne-era identity may not be as memorable to younger Kentucky fans as the Air Raid carved out during the late 1990's, but the wide-tackle six (six defensive linemen, two linebackers) was a staple of the Curci era.

Claiborne era's signature moment(s): In terms of popular memory it's probably the 1984 Hall of Fame Classic win over Wisconsin. History would bear out that this wasn't a small achievement, because Kentucky didn't win a bowl game again until 2006, a stunning two-plus decades later. Claiborne certainly can't be blamed for that, and in fact, in that context it makes his nine-win season pretty impressive. That 1984 team started the season 5-0 and reached a peak national ranking of No. 16. They hosted No. 10 LSU and were pummeled 36-10 and then lost to No. 13 Georgia (37-7) the following week. Of course, we can't overlook that team's 17-12 win at Tennessee.

There were other highlights outside of the '84 season, including wins over Clemson (1985), Florida (1986), Georgia (1988), North Carolina (1989) and LSU (1989).

Why it didn't last: He took the Kentucky job in his 50's and coached the program into his 60's, so it's not as though he was a young man, nor was it as though he was run out of town with pitchforks. Claiborne wasn't a "dud" by any stretch of the imagination, and there are significant reasons leading some Kentucky fans to hold him in such high esteem. You can't point to one or two things that ended his run in Lexington, but things just seemed to sputter towards the end. There was not obvious breaking point that made clear he couldn't lead the program successfully, but after that peak several years before his tenure ended, it seems like a common perception was that he just couldn't take the program to the next level from a point of semi-respectability.

Claiborne was probably the right coach to bring UK back to respectability and to establish a culture with more accountability and compliance, but he probably wasn't going to give the program that nudge to get over the hump and compete in the SEC. Solid if unspectacular. Those Kentucky teams were often regarded as physical and even punishing by opponents, but there weren't quite enough top-level athletes or dynamism on the whole.

While he might have been right for his moment (and there are those who believe his moment should have come sooner; certainly better than the sanctions), he was probably a set-up man for a coach who, ideally like Chip Kelly at Oregon, could have taken the structure, consistency and discipline and complimented it with more flare and swagger.

What we can learn: There's good news here. Even if Claiborne's early success wasn't followed by continued success or growth, it's still possible for a team to do something impressive even minus the preceding hype, and against the public narrative. By the time Claiborne took over the Kentucky job in 1982, the Cats had already suffered through sanctions, with much of Fran Curci's success de-legitimized in the public eye, but like Brooks (only sooner, perhaps in part because Curci himself suffered through much of the sanction-impacted seasons and gave Claiborne some distance from the penalties).

This is a reminder that a new coach does have a certain window of opportunity when he's establishing a new culture, making his own stamp on the program, building his own leaders, depth charts and systems, and Claiborne is a good reminder that a new coach can win quickly, even against the odds. He's also a reminder that you have to seize any window of opportunity and complement it with investments in recruiting budgets, coach salaries, facilities, forward-thinking approaches to recruiting, etc.

Claiborne made generous use of the redshirt allowance and that helped to build older, more experienced depth and created players who gave more to the program over a longer period of time in Lexington. That's a good strategy when possible.

We should also learn this: Don't take the "solid" for granted. Not at Kentucky. Chances are, even in a best case scenario, Kentucky's not the next Alabama. That means fans should be willing to endure the occasional five or six-win team, if all the other fundamentals and indicators are still favorable, because progress isn't always linear and sometimes there will be steps back. The program did regress under Claiborne, if you give him credit for building the 9-3 team and back-to-back winning seasons, but it didn't fall to such a level of misery that he should be remembered as an earlier-era Phillips.

It's also worth taking this: Don't take doing things the right way for granted. It's tough to quantify the significance of cleaning up a program's image after it has fallen into ill-repute, and that's what Claiborne did. While winning is ultimately what gets coaches hired, fired, promoted or richer, more than anything, it really is worthwhile to think about several factors when assessing a coach's legacy.

4. The Fran Curci era. What a tough example this one is. On the one hand, Curci attained a level of success on the field that, objectively speaking, far exceeds anything accomplished by anyone since. Considering his peak season was 1977, that's saying something. He shared an SEC championship in 1977 and elevated the program back to, or close to, the level Bear Bryant left it at more than two decades before that. Winning at Kentucky wasn't perceived to be as "against the odds" as it has been in more recent times (in part because of the program's history after Curci), but his best results were still probably better than most would have believed Kentucky would have produced, even at the time.

However, there was cheating. Not a little cheating, either. The NCAA said, even as they dropped big sanctions on the University of Kentucky, that the penalties probably would have been more severe if UK hadn't cooperated to the extent that they did.

"In a lengthy summary of the case, the N.C.A.A. said Kentucky representatives had offered high school prospects various gifts and inducements, including cash, clothing, free transportation, the use of automobiles, trips to Las Vegas, lodging, theater tickets, and, in one instance, a horse race" (New York Times, Dec. 20, 1976, "N.C.A.A. Places Kentucky on Probation for 2 Years").

Furthermore, coaches on Curci's staff were found guilty of giving money to Kentucky football players (not recruits) as a reward for good play.

It seems impossible to create watertight containers for separate Curci legacies. The bad is intertwined with the good, and was very likely directly related to the program's success during that time.

Curci's era's signature moment(s): Is there any question? The 1977 team, led by quarterback Derrick Ramsey, a by-committee rotation of running backs and a defense that surrendered 20 points twice all year (and never more than 21), spearheaded by Art Art Still, won its final nine games of the season after losing to Baylor in the second week.

Vanderbilt coach Fred Pancoast said, "Kentucky is the best team I've seen in the Southeastern Conference in a long time. ... Their defense is the best one I've ever seen in college football" (Sports Illustrated, William F. Reed, Nov. 14, 1977, "Togetherness pays off at Kentucky").

There were also winning records in 1974 (6-5) and 1976 (8-4, later adjusted to 9-3), the latter including a dominant 21-0 Peach Bowl win against North Carolina.

Why it didn't last: The cheating, the cheating and ... the cheating. Perhaps the success never would have come without it, at least in the tidal wave that it did, with all its national prestige and lofty rankings, but that's speculation. The cheating did Curci's program in. It was impossible for him to recapture the magic of '76 and '77 after the cheating became exposed and was punished with probation the spectre of malfeasance.

The NCAA's ruling in late 1976 prohibited that 1977 team from appearing on television in any of its games. The program's maximum scholarship allotment of 30, in 1977, was trimmed to 25. And the '77 team wasn't allowed to participate in a bowl game.

The scholarship restrictions, lack of TV exposure and the public revelation of impropriety surely hampered Curci moving forward, but it was perhaps the bowl ban imposed on the '77 team that leaves the greatest, "What if?" question. That team, it turned out, could have competed in one of the sport's biggest postseason games, and at one point there was even talk (see the earlier NYT story) that Kentucky and Alabama might have met in a bowl game, since they didn't have a regular season meeting. Imagine that: A New York newspaper writer pining for a Kentucky-Alabama football game.

What we can learn: Don't cheat. Oh, and don't cheat. Noticing a trend? It's not unique to Kentucky, mind you. It's an experience shared by countless programs through the decades, although in recent years schools who have engaged in underhanded tactics have learned to deal with the NCAA (and sanctions) in a way that, usually, allows for continued success or, at least, a quick rebuild. The NCAA has been less quick to impose the harshest of sanctions these days as well. But don't cheat.

Frankly, there's probably not a whole lot else to take from the Curci era, since the on-field successes are so difficult to evaluate detached from the rule-breaking, and since the game (and the world) has changed so much in the last 40-plus years.

WHY THIS IS KENTUCKY'S BIGGEST, BEST OPPORTUNITY

Again, it's tough to make the case that this is Kentucky's biggest, best window of opportunity for success without using the benefit of hindsight, and hindsight is only valuable when looking backwards; it has a limited value for future prognostications and even an evaluation of the present, except inasmuch as it gives some good lessons and may impart the kind of wisdom that should come with age.

But we can use hindsight. We can know, for certain, that Kentucky's past players, coaches and administrators did not, collectively, climb through any of those windows of opportunity to open the doors to a better, brighter future. No such judgment can be rendered about Mark Stoops, his assistants and their current or future players. The history has yet to be written.

Even throwing aside the hindsight consideration, there's a case to be made that, objectively (or as close to it as we think we can get), the Kentucky of 2017 is a more hopeful, more promising, more likely to succeed operation than any that preceded it in Lexington since Bear Bryant.

There's an assumption that rules are being followed, and there's good reason to believe that they are. For starters, in our personal experience covering the football program and its recruiting operation, there's no small number of hoops that need to be jumped through, T's crossed or I's dotted, that indicate the program is serious about staying above board. In fact, without going into too much detail, many of Kentucky's football and recruiting policies seem to be more restrictive (or to use less of a pejorative term, a stricter interpretation for the sake of compliance) than those in place at even other SEC schools. And that makes UK's recruiting success under Mark Stoops all the more impressive. There's also no reason to believe that non-compliance would be a pattern under Mitch Barnhart, a man who has taken the UK athletics program to greater heights, as a whole, than its ever been to, but also a man who has successfully, quietly, rehabilitated the images of many a university programs that haven't always had squeaky-clean reputations in the national media or public psyche.

Taking for granted an assumption of compliance, as is only fair in the absence of any evidence to the contrary (we're making this point only because NCAA investigations are common at so many schools, even in so many unlikely circumstances, that it must always be mentioned, at least, and in the context of the Curci and Mumme eras, and our evaluation of those eras, it's only fair), let's go to the facts.

1. Mark Stoops' win trajectory at Kentucky. Stoops inherited a program that failed to win a single SEC game in Joker Phillips' final season; a program whose final Phillips' era team lost to Vanderbilt 40-0 in Commonwealth Stadium; a program with an almost perfectly, predictably downward-pointing win graph chart; and he has simply reversed it, completely.

From two wins in Year One to five wins in Years Two and Three, apiece, to seven wins in Year Four, it's undeniable that Kentucky's win output is improving at an impressive pace. In fact, the pace is impossible to explain away by an appeal to secondary factors. Last year's schedule featured a tough slate of road games (Alabama, Florida, Tennessee, Louisville). Kentucky lost its starting quarterback in-season and subsequently started a little-known two-star JUCO transfer. The defense was still young. The special teams were not a major positive as an X-Factor. Turnovers did not, unpredictably, benefit Kentucky in a disproportionate way.

Kentucky won seven regular season games in 2016 and for arguably one of the first times in decades, such an achievement was not an act of overachieving. It was simply a team with improved talent playing at a higher level. It stands to reason, then, that as the program's talent continues to either plateau at a level higher than that of previous UK teams, or even rises incrementally, that the on-field product could continue to improve.

2. Kentucky is set up to follow 2016 with more success. Curci's program plummetted after that '77 co-conference championship team (see: sanctions, among other factors). Claiborne's '84 team was followed by four losing squads in a row. Mumme's declined precipitously after Tim Couch left Lexington (see: sanctions also). Brooks' declined as superb leadership wasn't replaced and as the next crop of lower-ranked expected overachievers simply didn't overachieve.

Stoops' fifth team at Kentucky has yet to win a game, but without question, the Cats are set up to make a little noise in the SEC East. Phil Steele has pegged the Cats fourth out of seven teams in the East, which is certainly above his historical average. Others have already predicted a win over Tennessee. Georgia nearly lost in Lexington last year. Florida has been far from a juggernaut in recent years and last year's debacle in the Swamp aside (a lot changed after that, remember), Stoops' other teams played the Gators very well.

Last year's team finished 7-4 after starting 0-2, all of those wins with returning starter Stephen Johnson behind center. The team defeated Louisville and Heisman Trophy winner Lamar Jackson on the road in the year's biggest upset. They did not wilt down the stretch like most Kentucky teams have in history. In so doing, they bucked the trend (or narrative, whatever you will) that Stoops' teams started strong but failed to finish (really, that was a Kentucky problem more than a Stoops' problem, and is easier to understand when you consider the impact of depth later in the year, and Kentucky's back-loaded schedule most years).

Kentucky returns as many starters as any team in the Southeastern Conference in 2017, and more than most teams in the country -- and that includes that starting quarterback, the unquestioned leader of the offense, and the best kicker in school history, who played a pivotal role in two big wins late in games.

3. The culture seems to be better. "Changing the culture" is a priority for any coach who takes over a losing program. Sometimes it's probably really an issue; other times it makes for an easy, recurring story. But in Kentucky's case there was clearly a culture problem when Stoops arrived.

There was an absence of leadership, a widespread apathy in the fan base, and a national perception, which had lasted for decades (with few, brief intermissions) and had served as a self-fulfilling prophecy that created massive hurdles. Even when things were going well, fans (and even players) seemed to be waiting for the hammer to drop. For the first part of Stoops' tenure it was even in his own face, after games in press conferences, as he searched for answers following the latest late-season defeat or second-half collapse.

There seems to be a new wave of legitimate leadership moving up the ranks in the program. Few imagined Johnson, at quarterback, would step in and step up in this regard, when Drew Barker went down. The team's top playmakers on defense are rising juniors so most figure to be well-positioned to give Stoops' squad two full years of lead-by-example visibility. Plus, some of those players are pretty vocal.

4. The talent is on the rise and it's not even a debate. This is something that has been written about here ad nauseam so it doesn't need to be rehashed in full, but it's the single-most important factor driving UK's improvement under Mark Stoops and it can't be mentioned often enough.

The "ceiling" talk for UK football was understandable in the past, because Kentucky's recruiting classes routinely ranked in the 50's or 60's nationally, at the very bottom of Power Five classes and below even some Group of Five schools. Now, it seems difficult to fathom how that went on for so long, but Stoops and his staff deserve all the credit for turning that perception on its head and obliterating it with a sledgehammer.

The biggest legacy Mark Stoops will ever leave Kentucky football are the elevated expectations for recruiting. No future coach will ever be able to make the case (nor will his apologists during bad times) that it's too hard to recruit good players to Kentucky.

5. This is the best Kentucky football staff in recent history, at least, and perhaps for a much longer period of time. There's no objective way to judge this but Kentucky has handed out contract extensions and raises that have made them competitive with reputable, established national programs. They're treating good coaches like good coaches, Stoops has made good hiring decisions when other coaches have left for other jobs, and the jobs at Kentucky have been made more attractive by former Stoops' assistants finding soft landing spots or taking big steps forward career-wise: Derrick Ansley at Alabama, Craig Naivar at (a suddenly powerful) Houston and now Texas, Bradley Dale Peveto still in the SEC, D.J. Eliot taking a raise to move to Colorado, on the heels of a Pac-12 division championship.

Eddie Gran has been a steadying influence on the sidelines but, just as important, another talent-amassing recruiting warrior who has expanded the program's footprint deep into South Florida. Hiring Darin Hinshaw was widely praised when it happened, because he had a good coaching track record and there was a general consensus that Kentucky would benefit from a full-time quarterbacks coach, and he hasn't disappointed, orchestrating Johnson's better-than-expected first year in the program when things looked especially bleak.

Vince Marrow has been Vince Marrow from Day One and the big story with him over the past two years has been moving from Ohio recruiting ace to bona fide national recruiting star, landing players from a variety of spots and winning high profile battles against powerhouse programs.

Steven Clinkscale has extended Kentucky's reach into Michigan. He wasn't the most heralded assistant coaching hire, but the defensive backs performed well enough at times last year, and he seems to be coming into his own in Michigan and Cincinnati, two improving pipelines for Kentucky's program.

John Schlarman's offensive line was up and down during his first few years on the job, but last year with almost exclusively his own players and years of his grooming, the unit blossomed into one of the most dominant trench gangs in the entire country, and one of the best in the history of the program. That unit returns a lot, and the staff is now leaning heavily on Schlarman's evaluation prowess when it comes to offensive linemen. Understandably so.

Lamar Thomas was plucked from Louisville and the receivers did play better last year than they did most of the time in Stoops' early seasons. They were especially productive against Thomas' old employer. And he reinforces Kentucky's newfound foothold in South Florida, as many South Florida coaches (and as could be seen by the naked eye) at the program's recent camps.

Matt House was deemed such a hit after his first year that there seemed little question, according to our sources even before his promotion, that he would be promoted to fill Eliot's void. And how often is the widespread assumption been that when a defensive coordinator leaves for a perceived step up (as Eliot's was, in title and in money, to say nothing of CU's 2016 success) that his underling's promotion would yield a net benefit to the program? Because that's exactly what the perception has been around the program.

Throw in Dean Hood, a man long coveted by Mark Stoops, to head a special teams unit that had already improved last year, and there are good things to be said about every staff member. That's not just public relations spin or an overly optimistic, gloss-over-the-downside take. The staff isn't perfect and there are great staffs elsewhere, but by resume, unit performance and recruiting success, you'd be hard pressed to find a knowledgeable Kentucky football follower who gripes about the guys on the payroll.

That's to say nothing of the most forward-thinking, successful recruiting staff and operation in the program's history, too, headed by Dan Berezowitz and bolstered by the likes of Josh Estes-Waugh and Luke Walerius, who are very active in the day-to-day roster-building that has proven so successful.

Move on to the strength and conditioning staff and, following the departure of Erik Korem, there can be little doubt that Kentucky has been a stronger, faster team with more endurance and fight in third and fourth quarters. Some of that is better players, some is more good players. But a lot has to be credited to Corey Edmond and Mark Hill.

Even the graduate assistants and other staffers (see: Tommy Mangino, who was instrumental in finding and helping to land 2017 receiver commit Isaiah Epps, a promising sleeper who is now on campus) have had more than their share of big moments.

PUTTING IT IN PERSPECTIVE

None of this guarantees short or long-term success for Kentucky, but there's a strong case to be made for this moment, the summer before the 2017 season, as the moment of greatest promise for Kentucky football since the early 1950's. There's a lot of hindsight in that assertion, but even trying to take the hindsight out, expelling it from the jury's consideration, there's still plenty of circumstantial evidence to suggest that the window of opportunity is bigger, and the sunlight shining through that window brighter, than it's been in a very long time.

The best thing that can happen for Kentucky football isn't necessarily just a huge step forward in 2017. That would help Stoops' cause and the program's, of course, but maintaining staff continuity, building on recruiting success and planting even more pipelines and furthering the recent investments into the program are clearly the path forward.

We know from previous "windows" that closed that there are a few things to avoid.

Don't break the rules. Don't neglect investments in the program. Don't start aiming low in the recruiting game.

But right now it seems as though the program would be well-served if Mark Stoops just keeps doing what Mark Stoops is doing, because after some struggles and criticism early in his tenure, he's had the right touch more often than not more recently.